In the early stages of my exploration into the craft of acting, I wrote about words. Words are the actor’s raw material. They are the beginning, the bedrock, the spark from which the entire performance ignites. They embody the soul of the playwright and serve as the thread that binds actor to character, character to story, and story to audience.

Any seasoned performer will affirm the exhilarating sensation of embodying the voice of Shakespeare, August Wilson, or Sarah Kane. To speak their words is to share in their genius — to serve as their medium and their muse. It is a rare and humbling privilege to stand in the company of giants.

️ From Words to Thought: The Next Step

If this is the first of my articles you’ve encountered, I encourage you to explore my earlier reflections on the actor’s relationship with individual words — particularly the small, often overlooked ones. These articles lay the groundwork for this next essential step in the actor’s journey: assembling words into thought.

“Acting can be described as the sharing of a given thought with an audience.”

This deceptively simple concept is the cornerstone of the actor’s craft. The process of learning how to think on stage — and crucially, how to reveal those thoughts — is what differentiates a competent performer from a compelling one.

Why Thought Must Come First

Many acting schools and instructors begin with emotional access, physicality, or vocal technique. These tools are, without doubt, essential components of the actor’s arsenal. But to start here, especially with a young or untrained actor, is to put the cart before the horse.

Unless one is performing mime (and even then, I would argue thought must be evident), the actor’s primary navigation tool is the text. Every gesture, every pause, every flicker of emotion must be driven by thought — the inner logic that fuels action. It is thought that governs:

- Physicality

- Rhythm

- Vocal inflection

- Emotional connection

- Timing and movement

- Subtext

- Tone and energy

To ignore this foundational layer is to risk reducing performance to surface-level mimicry. Before anything else, the actor must learn to think.

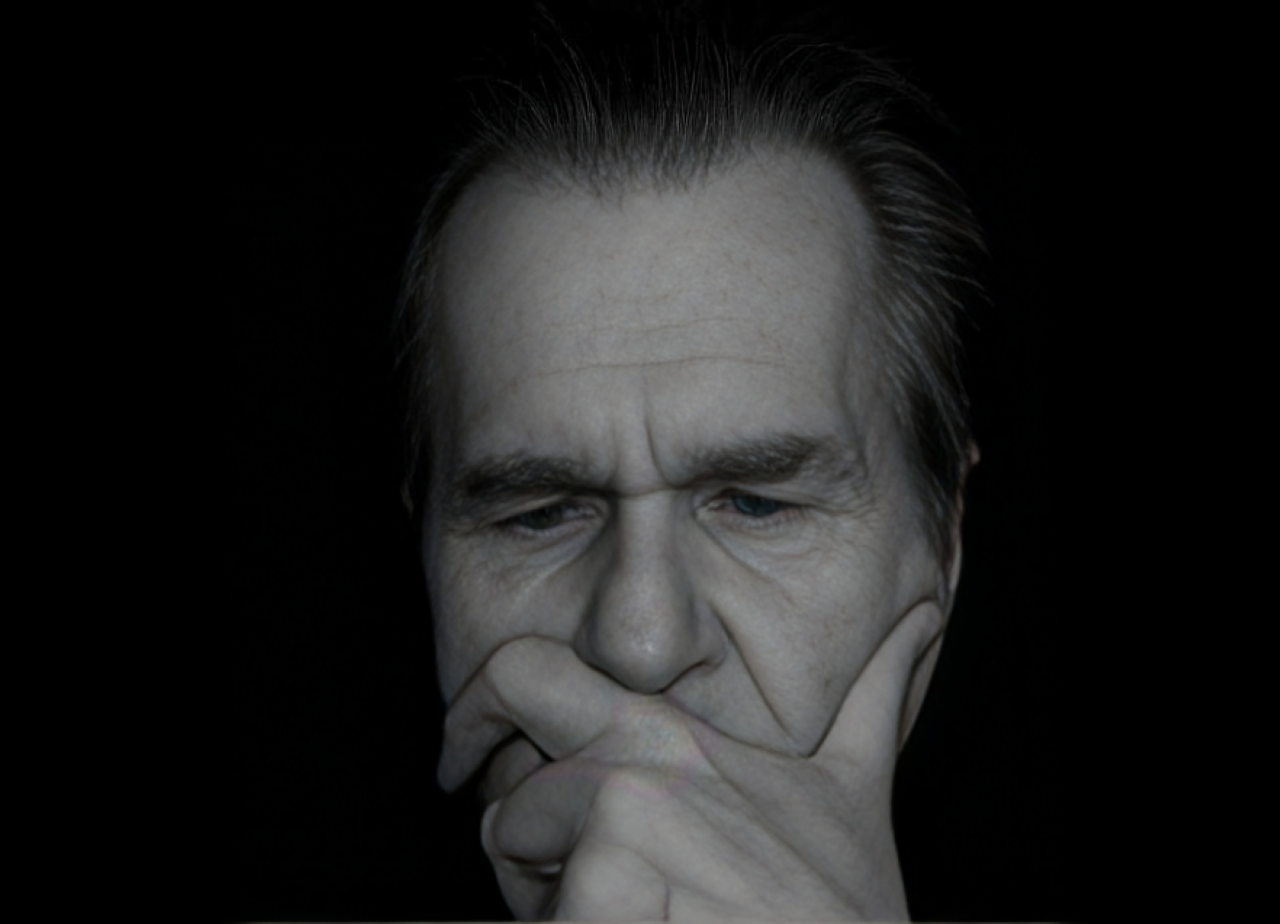

Thinking on Camera: The Secret Language of Stillness

Nowhere is this more critical than in screen acting. The camera is an unblinking observer. It captures not only action and dialogue, but every thought, every hesitation, every shift behind the eyes. This is the hallmark of the great film actor — the ability to do nothing while saying everything.

The audience must always see what the actor is thinking, whether in speech or silence. This is the true art of presence. It is in those charged moments of stillness — the “wind-up” before the line is spoken — that we connect most viscerally with a performance.

Laying the Foundation: Three Core Practices

To train this capacity for thought, actors must begin with the following three practices:

- Investigate the Meaning and Sound of Words

- Understand not just what you’re saying, but why you’re saying it.

- Let the music of the words inform the energy and rhythm of the thought.

- Explore How Words Combine to Form Thought

- Words are not isolated notes; they create melodic lines of thought.

- Recognise the emotional architecture built as thoughts unfold.

- Learn to Think on Stage

- Every new thought must be visible in the actor’s face and body — a shift, a breath, a pause.

- The moment before speaking is as important as the speech itself.

- Each shift in thought should feel like a trampoline — the spring that launches the line into life.

️ The Training Dream

One day, I hope to establish an actor training programme that begins precisely here — not with breath, voice, or movement exercises, but with thought. Around this core would sit the rich scaffolding of established methodologies:

- Stanislavski’s psychological realism

- Chekhov’s imaginative freedom

- Hagen’s authenticity

- Laban’s physical dynamics

- Classical structure and vocal work

All of these would serve the same aim: to develop an actor who thinks on stage and invites the audience into that thought process.

To be a truly great actor — to breathe life into language, to move and mesmerise an audience — one must learn how to think. Not simply think about acting, but to think within the character, within the text, and to invite the audience into that thinking.

This is not an abstract skill. It is visible, tangible, and vital. If acting is the art of transformation, then thought is the bridge that carries us from who we are to who we must become.

A Note of Concern

Each year, countless actors graduate from prestigious drama schools. Many of them can execute technical exercises flawlessly — emotional recall, physical improvisation, vocal projection. And yet, when placed in front of a camera or live audience, they cannot convincingly translate a thought. The mechanics are there, but the soul is missing.

So begin there.

Learn to think.

And let the thinking become your acting.